Exploring Polysemantic Universality with Embeddings

This blog posts documents my AI Safety Fundamentals project exploring the nature of polysemanticity with embedding models.

Overview

As part of the AI Safety Fundamentals Course, I have undertaken a short project relating to mechanistic interpretability. Mechanistic interpretability is the science of understanding the inner workings of AI models, and likely will be important in the safe advancement of AI. My project examines the validity of my intuitions formed after studying two key papers: Zoom In: An Introduction to Circuits and Towards Monosemanticity: Decomposing Language Models With Dictionary Learning. In particular, I investigate the phenomenon of Polysemanticity, where a neuron within an artificial neural network responds to multiple distinct features. One of the examples of a polysemantic neuron found in “Zoom In” responds to cat faces, fronts of cars and cat legs.

Polysemanticity makes interpretability research difficult. When a neuron responds to a range of inputs, it becomes challenging to determine its function. My initial assumption was that dissimilar features and relationships would exhibit consistent dissimilarity, meaning that knowledge of common polysemantic relationships would be transferable across models. The objective of this project is to test this assumption and find evidence for or against it.

I chose to explore this idea using embedding models. Embedding models compress natural language into a relatively low dimensional vector space where similar words are close, and dissimilar words are far (using the cosine similarity metric).

This blog post supplements the Jupyter Notebook found here: DanielJMWilliams/PolysemanticUniversality (github.com). If you are interested, I encourage you to run the notebook yourself, experimenting with different corpora, models and dimensions. The notebook contains three approaches to investigating polysemanticity in embedding models:

- Training minimal embedding models and observing the nature of the polysemantic relationships as dimensionality changes.

- Calculating the vector between dissimilar words and finding the most similar words to this vector. Then comparing these words across models.

- Finding the words most similar to vectors with a value of zero in all dimensions except one. Then comparing these words across models.

The following section details the experiments and their results.

Experiments

Approach 1: Observing Polysemantic Relationships as Dimensionality Increases

My first approach was to visualise how the relationships between distinct word vectors in embedding models changes as the dimensionality of the vectors increase. To test this, I set up a number of minimal corpora with a handful of words and used Word2Vec to train embedding models at varying dimensions. I plotted the word vectors on graphs to visualise their relationships.

Note that typically interference between words in embeddings is desirable, but in this experiment we have set up a corpus with four words that do not interfere and so are optimally all orthogonal.

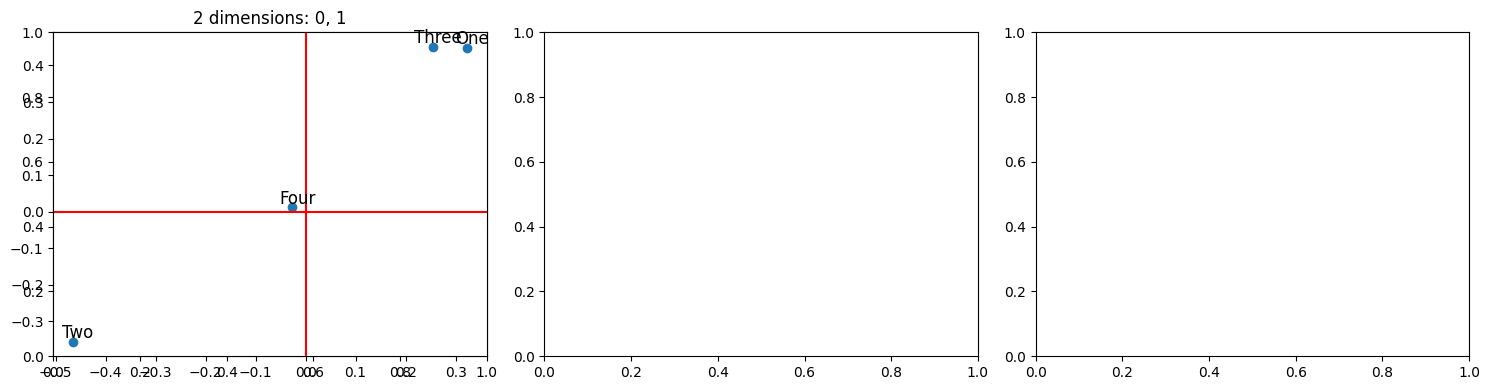

To begin with, I use “corpus_4”, which contains the sentences: “One”, “Two”, “Three”, and “Four”. Each word in the corpus is distinct and they occur independently of each other such that they represent four distinct features. This first graph plots all of the words in a 2-dimensional embedding model:

The similarity of the word vectors is determined by the angle between them. This can be observed visually, by imagining a line from the origin to one of the word vectors - any other points close to this line are similar. When looking at these graphs, it can be easy to think that vectors that appear far apart are dissimilar, but it is important to remember that it is the angle between them that matters. You can see, “Three” and “One” are similar and somewhat interfering compared to the other vectors. I consider this to be a polysemantic relationship.

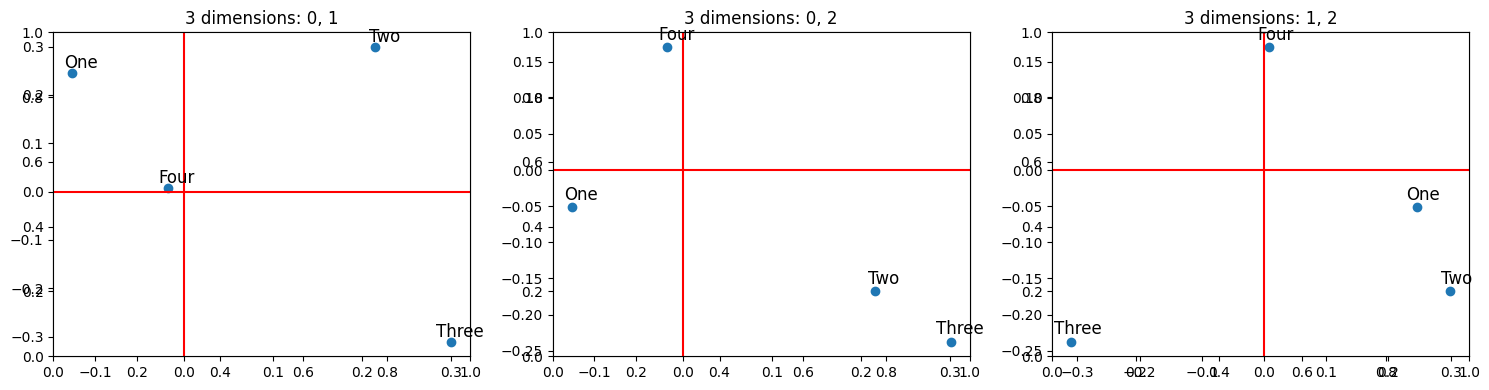

If we increase the dimensions to three and train the model again, visualising how each words in each dimension are related to each other, we get:  In the first graph showing the first two dimensions, “One” and “Four” seem quite similar, but in the other two graphs, they are almost orthogonal to each other. This seems approximately true for the other words in other dimensions too. The model is fitting four distinct features using three dimensions. It cannot use one dimension for each feature, so instead, while in one dimension the words interfere, in the others, they are distinct.

In the first graph showing the first two dimensions, “One” and “Four” seem quite similar, but in the other two graphs, they are almost orthogonal to each other. This seems approximately true for the other words in other dimensions too. The model is fitting four distinct features using three dimensions. It cannot use one dimension for each feature, so instead, while in one dimension the words interfere, in the others, they are distinct.

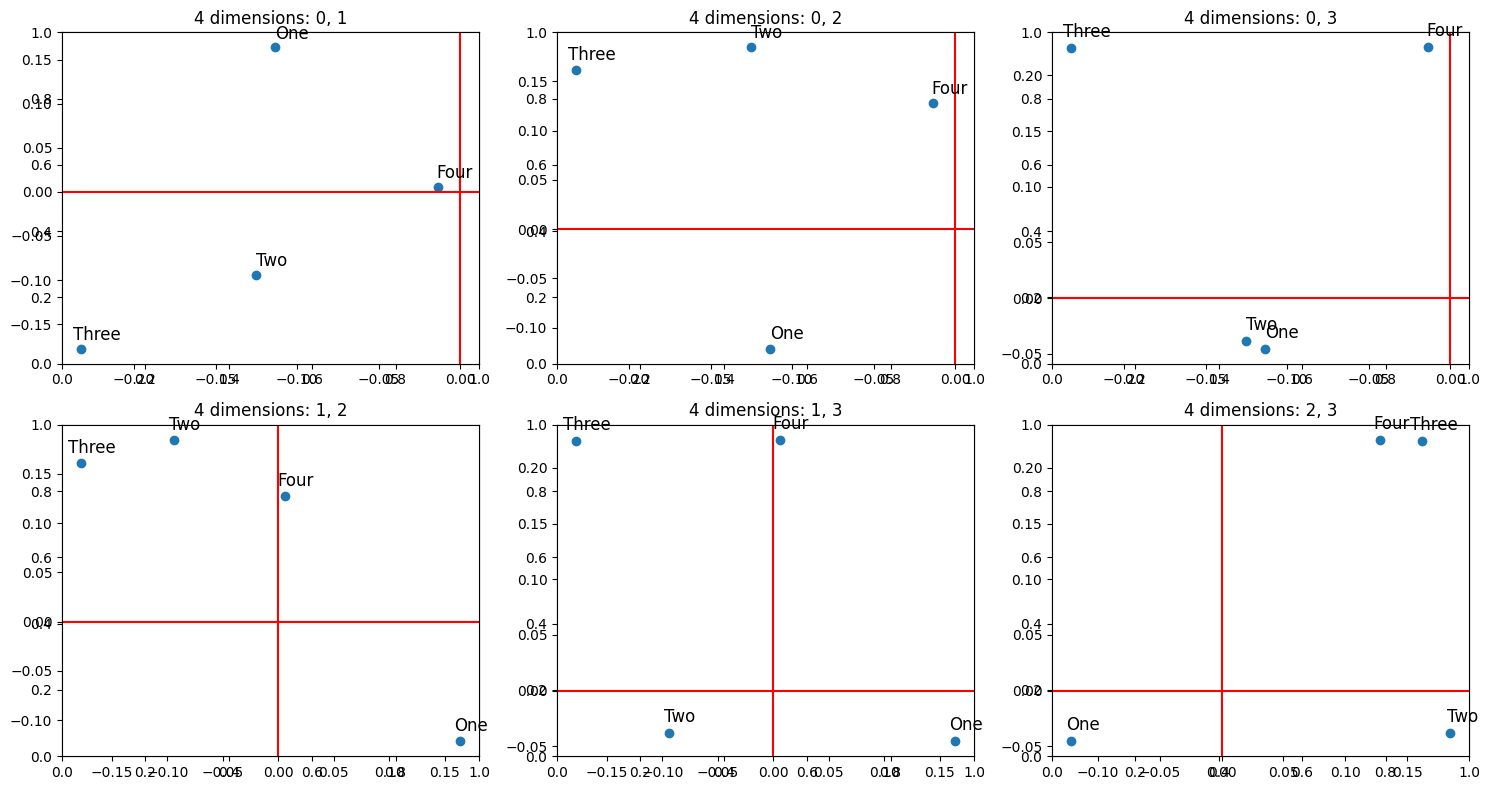

Now let’s see what happens when we increase the dimensions to four, where it would be possible for the model to learn one dimension per feature:  The model does not learn to use one dimension per feature, there is still interference between features in some dimensions. However, this makes sense as the model can actually represent many more features than dimensions using a binary encoding. In fact, with a binary encoding it could optimally represent 2^d features, where d is the number of dimensions. In this encoding, words are distinct if they are orthogonal in at least one dimension.

The model does not learn to use one dimension per feature, there is still interference between features in some dimensions. However, this makes sense as the model can actually represent many more features than dimensions using a binary encoding. In fact, with a binary encoding it could optimally represent 2^d features, where d is the number of dimensions. In this encoding, words are distinct if they are orthogonal in at least one dimension.

The Jupyter Notebook contains more graphs with different corpora, but I will not describe them here. If you would like to see them, check out the notebook: PolysemanticUniversality/PolysemanticUniversality.ipynb at main · DanielJMWilliams/PolysemanticUniversality (github.com) and run the code yourself.

I found the results of these tests difficult to interpret especially when the corpora contained co-occurring words. This made the approach difficult to determine whether polysemantic relationships are universal. What I did learn from these tests was that polysemantic relationships allow a model to learn more features than it has dimensions, and may even be learnt when the number of dimensions match the number of features.

Approach 2: Vectors between dissimilar words

Another approach to finding polysemantic relationships I took was to choose two seemingly unrelated words, compute the direction between their vectors and see what words are most similar to that resulting vector. The hope was that these words would be similar across different models, indicating that dissimilarity is consistent.

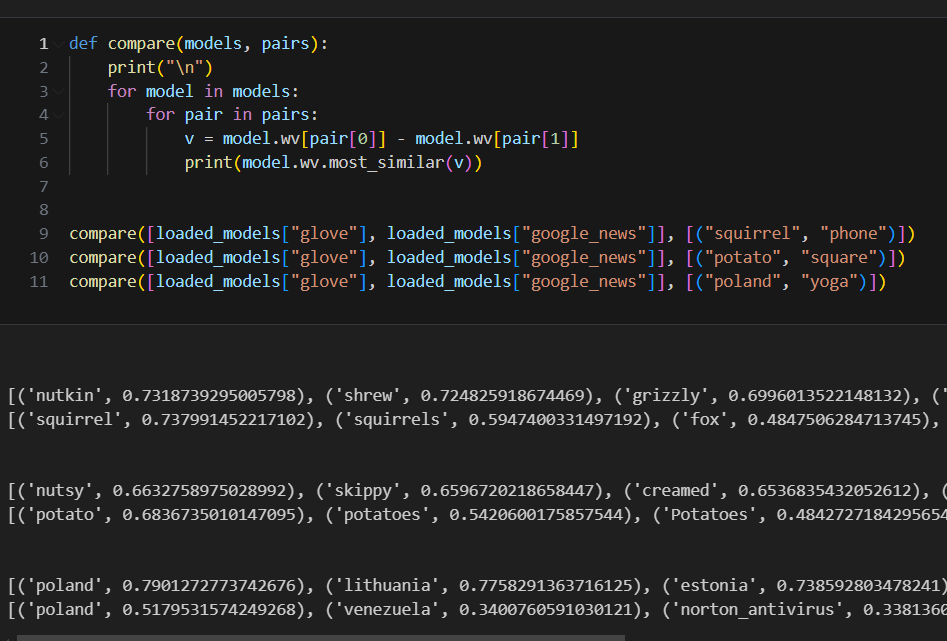

Here is the code along with a few sample outputs:

The output of the first compare , finding the most similar words between the word “squirrel” and “phone” produced different words in both the glove and google_news models. The glove model must have interference between the words “phone” and “squirrel” as it produces distinct words (e.g. “nutkin”, “shrew”). However these words seemed not to affect each other much in the google_news model as the most similar word to “squirrel” - “phone” is “squirrel”, with a lower similarity of 0.74. This could be because the “phone” vector has a low magnitude, or the two words do not interfere much. It also is likely to do with the sparsity of the embedding models. glove is only a 50 dimension model, while google_news has 300 dimensions.

The output of the second compare is very similar to the first, however the final outputs show that in both models, “poland” and “yoga” do not interfere much.

I chose words that intuitively seemed to be unrelated. This was of course unscientific and a finding the needle in a haystack approach. We want to find a vector reliably linking unrelated words - this is what lead me to the third approach.

Approach 3: Similar Words in Individual Dimensions

In Zoom In, individual neurons were visualised by generating an image that causes maximal activation of the neuron. For polysemantic neurons, this resulted in very different images for repeat runs. I wanted to try something similar with embeddings, finding the most similar words to a vector with a single dimension set to its maximum while all other dimensions remain zero. We will call these words the “dimension words” for ease of reference. If a dimension mostly responds to one kind of feature, i.e. is monosemantic, we would expect its dimension words to all be fairly similar to each other. If instead the dimension words are all seemingly quite different, it indicates the dimension may be polysemantic. We are interested to see if different models learn similar dimension words.

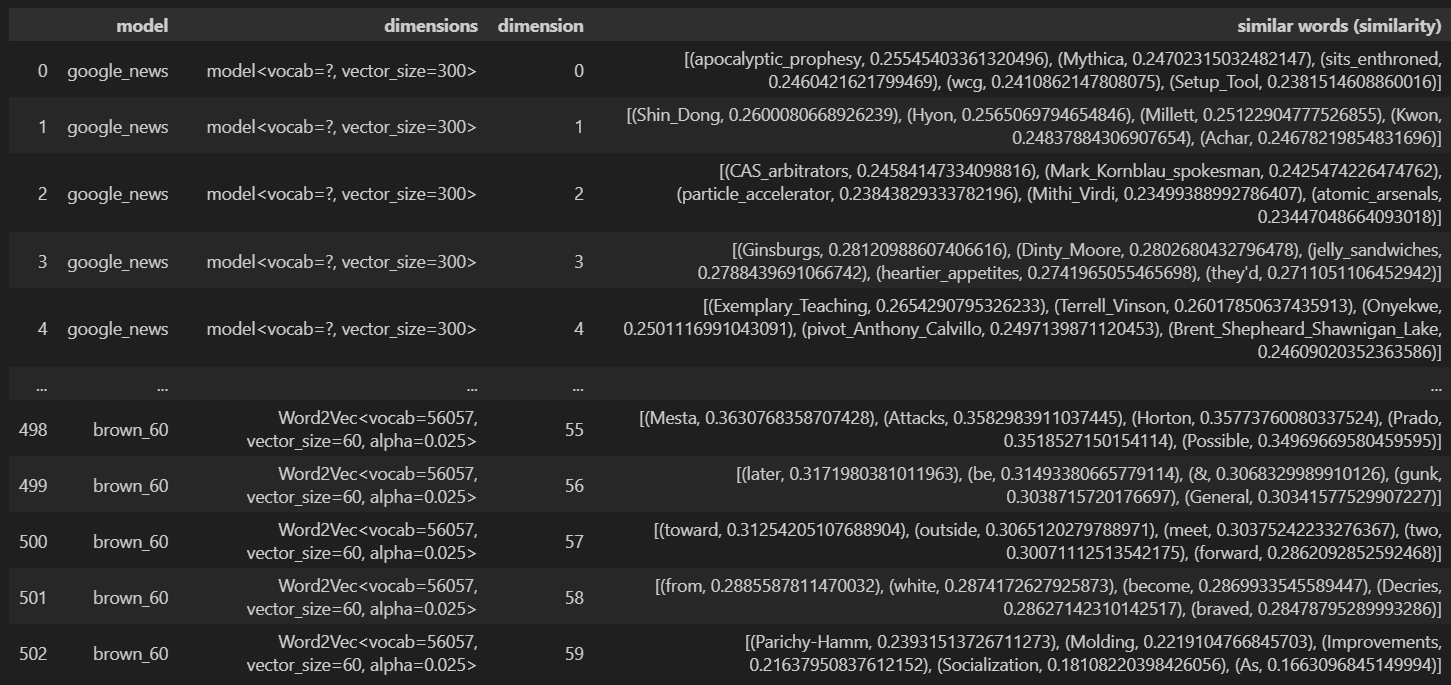

The code outputs the dimension words for every dimension in all of the models we tested into a table shown below and are saved in the output.xlsx file.

N.B. the models titled “brown_X” are Word2Vec models trained on the Brown Corpus, where X denotes the number of dimensions of the model.

To compare the models, we collate their dimension words, and list which dimension words pairs of models have in common. Here are the results:

| Model 1 | Model 2 | # Words in Common | Words in Common |

|---|---|---|---|

| google_news | glove | 0 | |

| google_news | brown_40 | 2 | also, until |

| google_news | brown_50 | 0 | |

| google_news | brown_60 | 0 | |

| glove | brown_40 | 0 | |

| glove | brown_50 | 1 | with |

| glove | brown_60 | 0 | |

| brown_40 | brown_50 | 56 | ?, A, Achieving, Advantages, Backbends, Boonton, Dairy, Eligibility, Goddammit, Impatiently, In, Meats, Months, Morale, Movies, Nightclubs, Norms, Of, Proprietorship, Repayment, Requirements, Secretion, Somersaults, Subjects, Sulfaquinoxaline, Syllabification, Thirty-four, Thirty-six, Trim-your-own-franks, Undergraduates, United, Vacations, an, are, available, be, became, been, between, could, does, due, during, ever, four, men, or, our, own, per, period, were, whose, will, without, would |

| brown_40 | brown_60 | 61 | ;, ?, Achieving, Advantages, Backbends, Dairy, Department, Eligibility, Goddammit, Her, His, Impatiently, In, Keerist, Meats, Molding, Months, Movies, Nightclubs, Norms, P.S., Proprietorship, Pugh, Repayment, Requirements, Seafood, Secretion, Somersaults, Subjects, Sulfaquinoxaline, Syllabification, These, Thirty-four, Thirty-six, Trim-your-own-franks, Vacations, Workmen, along, an, are, as, be, become, could, different, does, followed, for, from, million, off, or, our, own, same, up, water, were, whose, will, would |

| brown_50 | brown_60 | 70 | ””, “Ill”, “cant”, &, ), 7-5, ?, Achieving, Advantages, An, Astronomy, Backbends, But, Calves, Dairy, Deterrent, Eligibility, For, Frame, Goddammit, Impatiently, In, Keeeerist, Meats, Months, Movies, New, Nightclubs, Norms, Plants, Poultry, Proprietorship, Repayment, Requirements, Secretary, Secretion, Socialization, Somersaults, Status-roles, Subjects, Subsystems, Sulfaquinoxaline, Syllabification, Thirty-four, Thirty-six, Thirty-three, Trim-your-own-franks, Vacations, an, any, are, be, cent, could, does, economic, no, or, our, own, political, program, their, three, too, were, whose, will, would, you |

As you can see, there is little to no overlap with many of the models. The only models that have significant overlap are the Brown models of similar dimension size - this is not surprising as they are trained on exactly the same data and have similar dimensionality. I suspect that the cause of this is that a model’s dimension words tend to be quite obscure words from the training data. The most obscure words in the training data of a model likely do not appear in the training data of another. Looking at the top dimension words in output.xlsx, there are indeed many obscure words and phrases. Here are the top dimension words for the first 10 dimensions of the google_news model:

1

apocalyptic_prophesy, Shin_Dong, CAS_arbitrators, Ginsburgs, Exemplary_Teaching, souce, Gevry, muffle, costliest_natural_disasters, unleashing_torrets

More of these examples can be found in the output.xlsx file in the repository. Further investigation would be required to determine if these models all tend to have obscure dimension words.

The results of this test suggest that polysemantic relationships are not universal and instead depend heavily on the training data.

Summary

The purpose of this project was to test my intuitions of polysemantic relationships and see whether they may be universal. I investigated this with three different approaches, finding no evidence of polysemantic universality. I believe that this is due to the variances in training data used in different models having a significant effect on the learnt dissimilar relationships, however this requires further work to confirm. I did learn that polysemantic relationships allow a model to represent many more features than dimensions available to them and I now believe that my initial assumption of polysemantic universality is likely false.

Related

- Zoom In: An Introduction to Circuits (distill.pub)

- Toy Models of Superposition (arxiv.org)

- Towards Monosemanticity: Decomposing Language Models With Dictionary Learning (transformer-circuits.pub)

If you would like to discuss this project with me, feel free to contact me on LinkedIn.